THE VOYAGES

The vessels and passengers

Most of the Lacemaker emigrants sailed to Australian ports in one of three vessels, viz. Agincourt (destination Sydney), Fairlie (destination also Sydney) and Harpley (destination Adelaide). Other Lacemaker emigrants followed in smaller groups on other vessels. These included Andromache, Baboo, Duke of Bronte, Emperor, General Hewett, Harbinger, Hooghly, Navarino, Nelson, Norfolk, Walmer Castle and possibly others.

For further information on these vessels and their lacemaker passengers, check the Passenger Names and then the Shipping Lists

In Short ….

Passenger experiences varied: Immigrants faced different experiences based on the season, weather, and the ship's crew, significantly affecting their health and comfort during the journey. The Surgeon Superintendent played a crucial role in managing illnesses like measles and scarlet fever, which were common and often fatal.

Diaries provide insight: Several diaries and letters from immigrants detail life onboard, with notable examples including Joseph Tivey's and Thomas Turner's writings from 1848. These accounts offer a glimpse into daily activities and challenges faced during the long sea voyages.

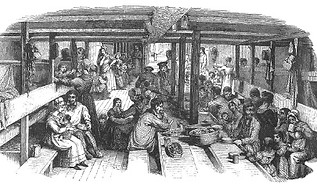

Ship accommodations were cramped: Immigrant ships typically housed around 260 passengers and 35 crew members in tight quarters, with single men, families, and women assigned specific, segregated areas. Conditions could become uncomfortable, especially during rough weather, leading to poor ventilation and sanitation.

For more detail, Read on ….

Life on the ships

The experience of the passengers on the immigration ships varied greatly depending on the time of year, the weather and sea conditions encountered. The immigrants were encouraged to take extra provisions to supplement and ease the bland and monotonous Government-provided rations, which were often of poor quality. The behaviour and assistance or otherwise of the ship's officers and crew also had a huge impact. This was especially true of the Surgeon Superintendent as his knowledge and competence were vital in treating the many ailments that afflicted the immigrants. Illnesses such as measles, whooping cough, smallpox and scarlet fever were contagious and often fatal.

An immigrant's diary

There are a number of extant diaries and letters written by immigrants, both those in cabin and steerage accommodation which describe daily life onboard. Some have been published; some are in private hands while others are held by Australian and overseas libraries. Some of these are available for research.

Two diaries written by immigrants during their voyages from England to Australia in 1848 are:

The Diary of Joseph Tivey; a steerage passenger on Bermondsey

Thomas Turner, Memorandum Book for the Voyage on Board the Baboo. Thomas Turner was a passenger with his family in steerage on Baboo, which also carried the lacemaker Mather family to Adelaide.

Another diary written by an immigrant in steerage is that published in the book humin hopes edited by Rob Wills. The diarist sailed on Constitution in 1855 which arrived in Sydney and the passengers and crew then spent time in quarantine at North Head. The book is available from https://www.pigfacepress.com/

Accommodation

Generally, the immigrant ships of the mid 19th century were made of timber, about 120’ long and about 30’ wide. They had two full decks, three masts and were either barque or ship rigged. Passengers were usually about 260 people with 30 to 35 crew together for about a 3 to 4 months voyage.

Both decks ran the full length of the vessel. The weather or upper deck was open to the weather and where the crew manned the various lines (ropes) to adjust the sails. This deck was also crowded with water butts (barrels), pumps, the small (rowing) boats, spare yards, capstans, companionways, deck houses and pens and cages for the fowls, pigs, sheep, goats and occasional cow that provided eggs and milk or were slaughtered for food during the voyage. The main deck below the weather deck, was where the quarters for the crew and passengers were located. Below this deck was the narrow space where the anchor cables (ropes), spare timber for the carpenter, passengers’ luggage and food stores were found hopefully above the water sloshing around in the bilges.

On the main deck the crew’s quarters were in the bows (forecastle) while the captain and his mates had small cabins in the stern. Between these quarters the immigrants were accommodated in three areas. The single men and youths were forward, the married couples and their young children were in the central area and single women were towards the stern but forward of any officers’ cabins. Usually the ships had double-deck timber bunks which ran along both sides of the vessel. Running down the centre of the vessel were two tables with benches fixed to the deck. Agincourt was an exception as it had the tables along the sides and the bunks doubled up down the centre. Perhaps this was a configuration from when it had been a convict transport vessel a few years before the lacemakers boarded her.

The vessels generally sailed well in fair weather. However, when the wind and sea “got up”, the voyage could become very uncomfortable with the passengers confined to the main deck while the vessel rolled and pitched in the rising sea. The captain was more interested in fast times than in passenger comfort. Slow trips cost him time turning his vessel around and earning commission on his next load. He therefore tried to keep the wind bearing from his stern, but slightly to one side of the vessel or the other. This caused the ship to rise and fall (pitch) on the waves from bow to stern and to roll from side to side at the same time, in an irregular, corkscrewing type motion that upset even the sturdiest of stomachs.

Often a ship’s captain headed down into the Roaring 40s to pick up the strongest winds. In these circumstances, passengers were usually confined below decks with hatches covered and battened for days if not weeks on end in poorly ventilated, damp and unsanitaryconditions.

More information about Ships and Sea Voyages

Life aboard an Emigrant Ship – Tulle Issue123 p9

Ship Types and Descriptions – Tulle Issue104 p28

Those Other Ships – Tulle Issue110 pp7-15

Those Other Ships – Tulle Issue112 pp5-8

Agincourt Press Clippings – Tulle Issue112 pp9-10

Emigration Papers – Surgeons Superintendent – Tulle Issue112 pp11-15

Walmer Castle – Press Clippings – Tulle Issue112 pp16-17

A comprehensive account of life aboard the immigration ships from Britain to Australia during the nineteenth century can be found in Robin Haines' book Life and Death in the Age of Sail: The passage to Australia, University of NSW Press Ltd, Sydney, 2006

Ship Harbinger

Immigrants on the weather deck

Immigrants' accommodation on the main deck

Sydney Cove

Ship Norfolk

Onward Journeys

The ships carried their lacemaker passengers to Port Adelaide in the Colony of South Australia and Port Jackson (Sydney) and Port Phillip (Melbourne and Geelong) in the Colony of New South Wales. After giving their details to the immigration clerks and disembarking, most of the lacemakers made their way into the nearby towns of Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne. For those onboard Agincourt, most bypassed Sydney for West Maitland and Bathurst.

The Colonies and the towns in 1848 are described in Places>Australia

The Shipping Lists

Check the lists of the passengers aboard each migration ship and information about the ship

Ship Sailing Route

The map shows the likely route of the immigrants' ships from England to Australia before 1850. To cross the Indian Ocean, the ships usually sailed just inside the Roaring 40s with strong winds pushing them eastwards before turning north to the destination ports of Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney.

In later decades the ships often sailed much further south to use the very powerful winds in the 50 degrees south latitudes.